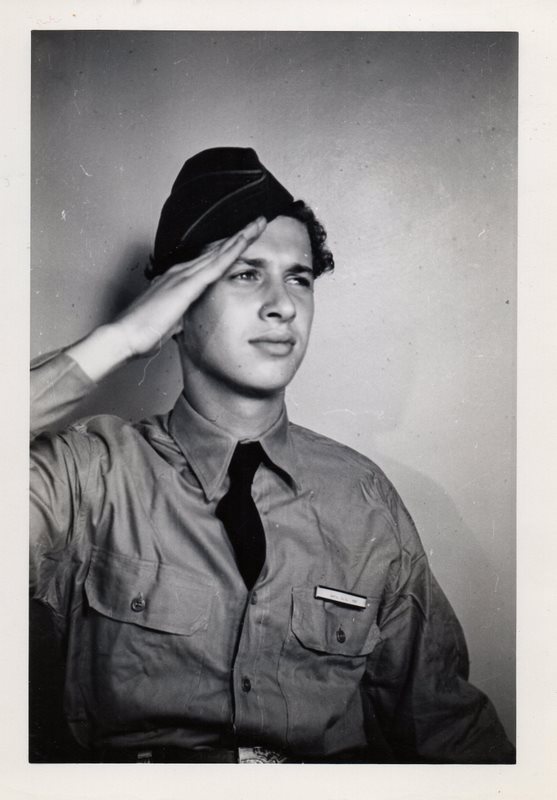

WWII Naval Veteran and Electrical Engineer

Celebrate Our Veteran gives voice to the stories of the U.S. military veterans living amongst us. The actions of these brave and dedicated people, who have served our country both in active military duty as well as administrative positions, have and continue to contribute to the protection and preservation of us and our country.

We hope that this section of our paper is an opportunity for our community to hear and see veterans with new eyes, and for veterans to receive recognition and honor for their experiences and life journeys.

This month’s Celebrate Our Veteran recounts the story of Norton Davis, as told in his own words. This is part one of a three-part series. Click here to read Part 2.

by Melissa LaScaleia

“I was born in 1925. World War II broke out one Sunday when I was a senior in high school, and everyone went down to enlist on Monday. But I was only sixteen years old, and my mother wouldn’t sign anything, so I couldn’t enlist.

I finished high school in June of 1942 and didn’t turn 17 until the end of July. I made an agreement with my mother and father that I would go to college, but that the day they called me, I’d put down my pencil and go and not request a deferment. And that’s what happened.

I went to Purdue in Indiana and studied electrical engineering production and management. In those days, because there was a war, there was no such thing as being able to take off for the summer. We attended school fifty weeks a year, with one week off between Christmas and New Year’s Day.

There were no limits as to how many credits you could take, so I took 23 credits my first semester; 27 my second, and I don’t remember what I took after that. But by the time they called me, in October of 1944, I had just one semester left, and I did that after I got out of the service.

Most of the people who were drafted where I was living in Indiana wanted to go into the Navy for two reasons: one is that you sleep in a warm bed, you don’t sleep in the mud. The other is that these guys grew up in the Midwest and they wanted to see the ocean.

I came from New York and grew up in the Bronx. I knew what the ocean looked like, but nevertheless…my brother-in-law had a friend who was a dentist and worked for the Army at the induction center where I had to go to receive my intake physical.

My brother-in-law fixed things for me, and told me to ask for the dentist when I arrived— that he would assign me.

So I saw him and introduced myself, and he took my papers and put a big letter ’N’ on them for Navy. Everybody saw this, and came running over to him for their assignment. And he said, “Oh, no, no. We got special word from Washington about him.”

So I was in the Navy.

At this time, there was a program called the Eddy Test. It was named for Captain Eddy, a naval officer from Annapolis. There were a lot of new electronics for warfare that they were developing, and somebody had to know how to repair and adjust them so they were reliable.

There was a device that was so secret at that time, that if I told you about it, I’d have to kill you; it was a piece of equipment that would tell pilots while they were flying if an aircraft in their vicinity was that of a friend or an enemy.

The highest priority that the Navy had was training people via this program so equipment like this could be maintained and fixed. And since I had so much education in electrical engineering already, I was in that program.

I started out by attending boot camp in the Great Lakes outside of Chicago. Then they sent me to the Navy offices in midtown Chicago for three months, on the corner of State and Lake Street. The Navy has a protocol— that always there is someone walking around making sure there are no fires— it’s called the fire watch. And late one Sunday, night, I was on duty on the twelfth floor.

So I had a few friends there, and my wife, and we were having a party, listening to music on the radio and dancing. And all of a sudden, the elevator door opens, and Captain Eddy walks out.

He waved at us and went back into his office. Twenty minutes later, he went back to the elevator, and left. Thirty minutes later, he returned carrying two big bags of groceries.

And he came in where we were and set them down on a counter in the kitchen and said, “If you guys are going to have a party, then you should do it with some drinks.” Then he pulled out some drinks and chips, wished us a good time, and walked out.

That’s the kind of guy that we were working for.

In Chicago, I learned all the basics— it was called pre-radio. They used to say, there’s the right way, the wrong way, and the Navy way. We had to relearn everything the Navy way.

From there I went to Corpus Christi in Texas, to specialize in aircraft.

Every week we learned how to fix a different piece of equipment; we also had to stand duty.

One day, when I was the fire watch, the movie theatre caught fire somewhere in the back where the equipment was. And by the Navy rules at that time, I was in charge of the fire. So I had everybody joining in to pull hose. I headed to the back where the fire was to get all the mail out, when someone jumped in to help me. But he got caught and disoriented by the smoke and the next thing I knew, he was walking inside instead of outside. So I had to run in and grab him and get him out.

From there, I was supposed to go to the Pacific because the U.S. was about to land on the Japanese Islands. But I didn’t carry a gun, I carried a meter and a screwdriver. They needed guys with my training who could keep that equipment operating.

But we got lucky. After the U.S. dropped the bomb, we didn’t go; then they decided to discharge everybody. They did this according to a point system.

For every month that you served you received a point, and after you accrued enough, you would be discharged. So they sent me to Norfolk, Virginia. I had about three weeks left until they would send me to be discharged.

And while I was in Norfolk, I was assigned suddenly to a brand new ship that was making its first voyage to the Mediterranean to get all its bugs and kinks out.

They had a rule in the Navy: if you’re on shore and your numbers come up, you get discharged. If you’re at sea and your numbers come up, you don’t get discharged until you’re replaced, and there were no replacements in our standards.

So I went down to the office and talked to the clerk and said, how do you get off the draft? And he said I can’t do anything about it, you have to go to Atlantic Fleet Headquarters.

So I ask for the phone number, and I call them up. And the phone just rings and rings and rings, then some old guy picks up whom I take to be the janitor. So I tell him what my problem is, and he tells me: “Well all the gentlemen are at lunch. They won’t be back until about 1pm. When I see them, I’ll tell them your problem.”

So I thanked him and hung up.”

To be continued. Click here to read Part 2.