Vietnam War Veteran and POW

“Celebrate Our Veteran” gives voice to the stories of the U.S. military veterans living amongst us. The actions of these brave and dedicated people, who have served our country both in active military duty as well as administrative positions, have and continue to contribute to the protection and preservation of us and our country.

We hope that this section of our paper is an opportunity for our community to hear and see veterans with new eyes, and for veterans to receive recognition and honor for their experiences and life journeys.

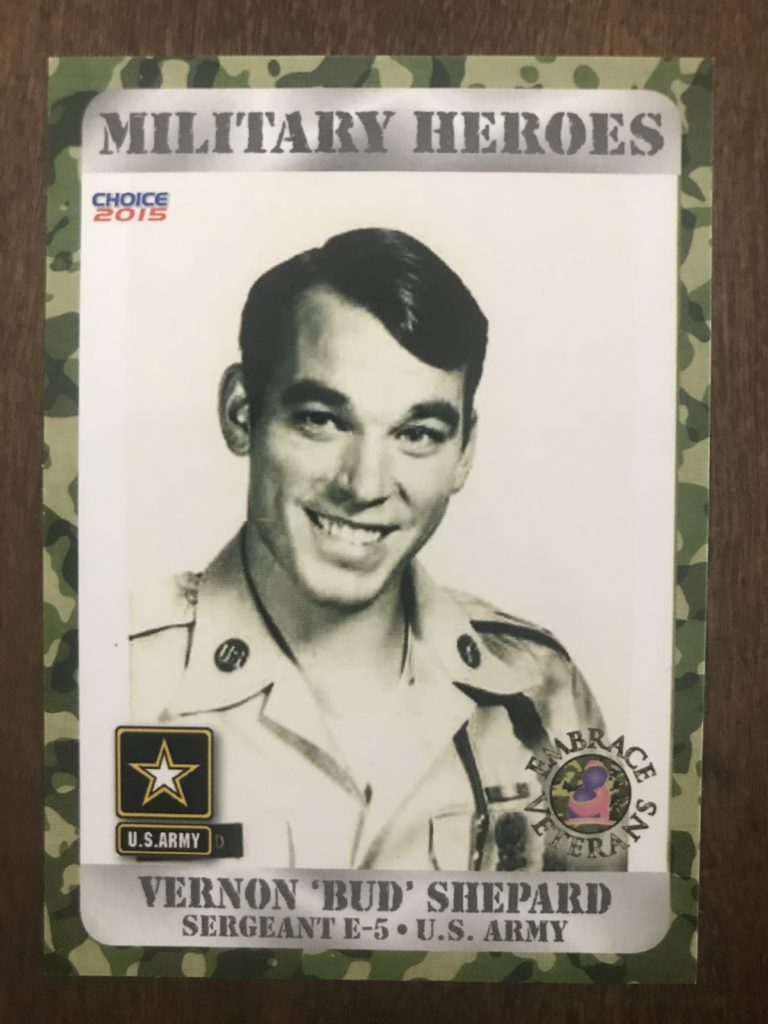

This month’s “Celebrate Our Veteran” recounts the story of POW veteran Bud Vernon Clark Shepard as told in his own words. This is the first of a three-part series. Click here to read part 2.

by Melissa LaScaleia

“Bud Shepard was born in Akron, Ohio on July 19, 1948. In 1967, at the age of nineteen, he was drafted for Vietnam. He had been working construction jobs every summer throughout high school, and that summer, he was working as a brick mason.

“When I got the draft notice,” Bud says, “I thought that if I could go into the army as a brick layer, it would be more beneficial for both me and the army.”

The only caveat was that Bud would have to enlist, which would be a three year term, as opposed to a two year draft. He decided to take his chances, and enlisted as a brick layer.

He was sent to Fort Leonardwood, Missouri for advanced training. But when he arrived, instead of enrolling him in masonry school, they sent him to learn carpentry. He was none too thrilled, but finished at the top of his class. When he completed training, they didn’t have any need for carpenters or bricklayers, so they sent him to Fort Knox, Kentucky, where he was assigned to an armored cavalry unit, the 194th Armored Brigade.

“I wasn’t expecting this at all,” Bud says. “Now I have a three year term, and I’m not doing what I enlisted for. They assigned me to a tank unit. There was a new tank coming out, called the M551, the Sheridan. And I was selected to field test and be part of the evaluation team for this tank that had a laser beam missile in it that could shoot a fly off an apple. I started out as a tank driver, then I became a tank gunner, and finally, a tank commander.”

Bud was asked to select his preferences for where he wanted to carry out his term of service. For his domestic choice, he selected Hawaii. For his foreign choice, he selected Vietnam.

“I wanted to go to war,” he says. “I wanted to experience that. I didn’t want to get sent to Germany. I was looking for excitement. Since I volunteered, naturally they would take me.”

Bud returned home and married his girlfriend at the age of nineteen, before he was sent to Vietnam.

“I didn’t want her to leave me,” he says with a chuckle, “so I decided to marry her.”

Bud was assigned to a helicopter unit, the B Troop 7/17 Air Cavalry unit. He was initially assigned to the mail room. The presiding commander looked at Bud’s personal record, saw he was a decent soldier, and wanted him to chauffeur the colonel around the base and work in the office.

Bud was eager for excitement though. He didn’t want to be a colonel’s orderly. He approached the captain to ask for a change of scenery.

“I said to him, ‘I really came over here to fight a war.’ And he looked at me and said, ‘We have these jobs called aero scouts. But you can’t be assigned as one, you have to volunteer.’ I didn’t know what an aero scout was, but I volunteered.

“I soon found out why you had to volunteer; your likelihood of surviving the duration of the war in this position was slim. Aero scouts flew a helicopter called a L-O-H, a light observation helicopter, which can fly slow and low to the ground. Only two people could fit in one, a pilot and a co-pilot observer.

“I was trained as a pilot too, in case the pilot was shot. Our job was to fly at treetop level and try to find the enemy. Flying at that height, you could usually see the smoke from their campfire cooking, or different things they left behind. We flew in teams of two, one helicopter at treetop, and the other higher up for protection— then we’d switch.

“If we found them, we’d radio in the information and within minutes, a COBRA, a giant gun ship that is very fast and cannot fly low, would come in and annihilate the area. We were called the hunter-killer team. We acted as the scalp hunters, and the COBRAs were called the undertakers. This was the only way to find the enemy, because there is so much canopy in that country, they were very well hidden.

“So it was highly risky and you never knew what to expect. The enemy knew if they shot at us that would give their position away, and then we’d call in the heavy guns. But if they knew we saw them, and we were so close at times we made eye contact with them, then they’d open fire. We’d often get back to our camp and see bullet holes in our helicopter that we hadn’t noticed.

“You have to be a little bit of an adrenaline junkie to do this. I actually really enjoyed it. You could quit at any time, on the spot. I did it for four months. I could see monkeys in the treetops jumping up and down, that’s how low we flew….

“We were stationed near the city of Ban Me Thuot in the province of Quang Duc about 120 miles northeast of Saigon. We were out in no man’s land. We had tents and outhouses; we didn’t even have a mess hall and would eat c-rations. On the days I wasn’t flying, I used to do garbage runs. I would collect all the trash and we’d burn it. The South Vietnamese children would hear the truck fire up and they’d come running to ride in it and help me.

“They would dig through the trash to see if there was anything that they could use. They were so poor and starving, that I would see them collecting spoiled milk that we had discarded and gulp it down on the spot. While I was there I was promoted to sergeant. But I still drove the truck when I wasn’t flying because I enjoyed the kids.

“One time a little kid stepped on a rusty can, and I took him back to the compound and stitched his foot up for him. But I used to wonder if he was all right after that because their conditions were so bad, I wondered if he received proper care to prevent infection.

“In our rations, we were given cigarettes, and the guys that didn’t smoke would give theirs to the kids. So you’d see 10-year-old kids smoking.

“On November 2, 1969, they needed somebody to go out on a mission. I wasn’t supposed to fly that day, because I had flown on the 1st, and they would always give you the next day off. There was a pilot named George who had seven days left before going home and he wanted to fly one last time, so he volunteered. And nobody wanted to be co-pilot with him, so I volunteered to fly with him.

“We went out, and the day was normal. We didn’t see a lot of activity, and we were on our way back to base camp. I was flying at that time and I liked to fly really low even though it wasn’t required at this point. We were following a curvy road, and I was zigzagging, having a good time, following the curves. We were laughing and done for the day and just enjoying it.

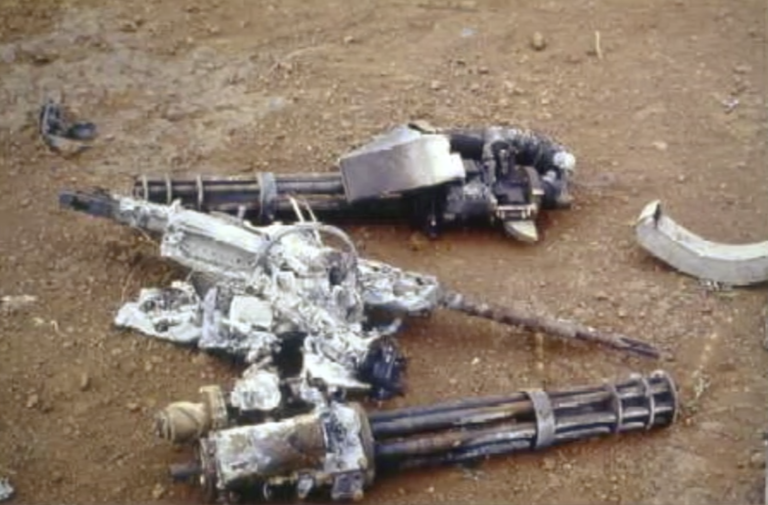

“All of a sudden, we came around a curve in the road and saw about fifteen of the enemy. They were digging a huge pit in the road to build a structure to put a machine gun on top of it. They were dangerous because it was a 51 caliber machine gun that could traverse 360 degrees.

“When I saw it was a fresh dig, and the enemy was right there, I circled back around and handed the controls to George to take over, and I got my grenades ready to throw. But George, instead of making a pass over them, he hovered over them. I don’t know if he was shocked, or just not that fresh, but in the moments that passed, I could see them and they could see us. We were staring at each other. And we were a wide open target.

“I was shot in the foot. The helicopter was destroyed on the bottom, and that’s where the fuel is. So the fuel fell out. The radio transmitters are located under the seat, but they were destroyed, so we couldn’t communicate with our wing man helicopter.”