Vietnam War Veteran and POW

“Celebrate Our Veteran” gives voice to the stories of the U.S. military veterans living amongst us. The actions of these brave and dedicated people, who have served our country both in active military duty as well as administrative positions, have and continue to contribute to the protection and preservation of us and our country.

We hope that this section of our paper is an opportunity for our community to hear and see veterans with new eyes, and for veterans to receive recognition and honor for their experiences and life journeys.

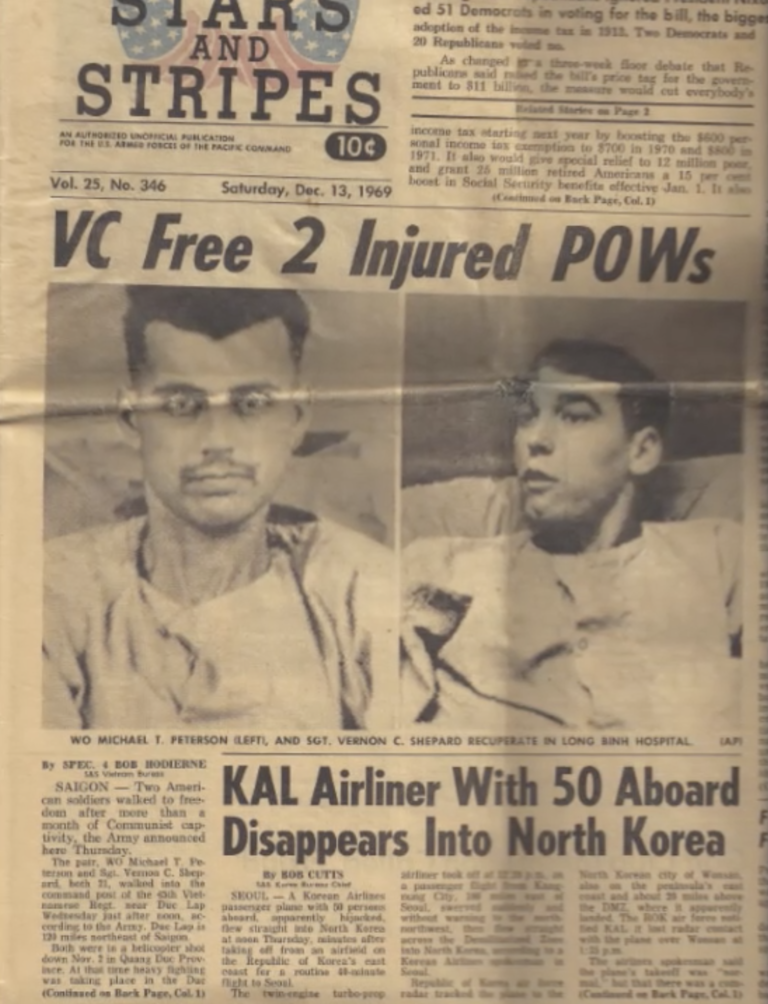

This month’s Celebrate Our Veteran recounts the story of Bud Vernon Clark Shepherd, as told in his own words. This is the final chapter of a three-part series, continued from last month. Click here to read part 2. Click here to read part 1.

by Melissa LaScaleia

“Then they took me over to a hole in the ground that was about eighteen inches by eighteen inches,” Bud says. “And the next thing you know, a doctor came out of this hole. He looked at my wound in my buttocks and he had this huge hypodermic needle and motioned me to bend over.

“I didn’t know what he was going to do, but to my relief, he began squirting the wound; then they took me into the hole which was an underground hospital. While I was in there, they bandaged it up they best it could. And then took me back, blindfolded me and tied me up again.

“After being with the North Vietnamese for a time, I grew to respect them a lot. They used their resources to the max. If we threw a tire or a can away, they’d find a use for it. They were very resourceful with what they had. They didn’t waste anything.

“They eventually brought us to a jungle camp, where they shackled us and put us in a human-sized cage. We were fed very minimally, and only twice a day. Jim and I were in the camp by ourselves for a couple of days before they also found the two others from the COBRA. We were there for a week, and during that time they’d take us one-by-one into the jungle and ask us questions.

“One day, they took the two who were less wounded away. They could walk and I found out later, they ended up being in a prison camp in Cambodia for six months, and then Hanoi, where they were prisoners for three years. But because another of my comrades Pete couldn’t walk and travel, and because I couldn’t walk as well as the others and was also the lowest ranking one amongst us, I was left behind to care for him.

“During our time in the cage, a couple of South Vietnamese POW soldiers who were with us, escaped and they never found them. Because the North Vietnamese couldn’t find them, they had to evacuate the camp— else the risk of discovery was too high.

“So we were prisoners of war for 38 days. They put Pete in a hammock and carried him. The first night, they tied us up to a tree and left us there. We thought that they had abandoned us.

“In point of fact, they had decided to let us go. They told us that they were going to release us for humanitarian reasons. I think that they sensed that if they didn’t release us, we were going to die. So prior to our release, we had to first write a statement that we were criminals, had invaded their country, and were the enemy. They signified our release with a ceremony to make it official.

“They hung the North Vietnamese flag in the jungle from the trees and built a bamboo podium. They shamed us a bit, and kept saying we were criminals. Then they gave us clean North Vietnamese uniforms to wear, and gave us detailed directions for the terms of our release.

“A few hours beforehand, they had released two South Vietnamese prisoners and gave them directions to an American fire base. They gave us directions to a road and told us when we reached it to lay down in it. The South Vietnamese prisoners were instructed to send an unarmed jeep to come and pick us up in the road. These were the terms of our release. Our prison guards warned us they would be watching us from the jungle, and that if anything went wrong, they would shoot us on the spot. Then they let us go.

“So I trudged out of there, carrying Pete to the road. When we reached the road, I laid Pete down in it and sat beside him. We must have been close to a village, because there were people walking by, and bicycling by us.

“And while we’re out in the road, a South Vietnamese patrol came by and they saw we weren’t the enemy, and they start circling around us, trying to protect us. And there was no way for us to tell them to stop. We were worried they were going to get us killed.

“Luckily Pete got their radio which was tuned to the frequency of the fire base, and told them the South Vietnamese soldiers should be arriving to the base soon with instructions about how to retrieve us.

“So finally the soldiers left. And we’re just laying in the road as people walk and bicycle by us. Finally a jeep came, driven by a soldier from the fire base and loaded us in. And on our way to the fire base, we saw the two South Vietnamese who were in charge of our safe transfer— they had taken off first chance they got without a care for us. So we were ultimately lucky that that patrol came by or we would have been laying in that road for a lot longer.

“When we got to the base, they air lifted us out and took us to the hospital. As soon as we arrived, the CIA joined us and separated Pete and I, and interrogated us to get as much information about the enemy as possible.

“Within a week, I was sent back to Fort Knox in a stretcher. And still the CIA interrogated me. If you Google search my name, you can listen to the debriefing— it’s still on there.”

Bud thought he would be eligible for early discharge, but he wasn’t. He finished his enlistment first, then was discharged.

“My first marriage lasted about ten years or so,” he says. “My current wife, Pat, and I got reunited at our twenty-year high school reunion, and found we were both single parents. She was living and teaching in Greenville SC, and I was working in management for the USPS in Ohio. After we got married, she moved back to Ohio. One weekend it snowed almost three feet; we had both retired, and my wife said, ‘It’s time for us to move South.’”

So they moved to Myrtle Beach, where they’ve been happily and warmly ensconced for the past ten years.

“I still have that uniform that they released me in,” Bud says. “I still have the blanket that they blindfolded me with, the cup I ate out of the boots I wore. I keep all that tucked away.”

Visit www.youtube.com and type in “Veteran’s Breakfast Bud Shepard” to watch a video of Bud’s personal testimony of his time in Vietnam.