A WWII Navy Veteran Who Served In the South Pacific: Part 1 of 2

Celebrate Our Veteran gives voice to the stories of the U.S. military veterans living amongst us. The actions of these brave and dedicated people, who have served our country both in active military duty as well as administrative positions, have and continue to contribute to the protection and preservation of us and our country.

We hope that this section of our paper is an opportunity for our community to hear and see veterans with new eyes, and for veterans to receive recognition and honor for their experiences and life journeys.

This month’s Celebrate Our Veteran recounts the story of Bob German as told in his own words. To be continued in next month’s Celebrate Our Veteran column. Click here to read Part 2.

by Melissa LaScaleia

“I was born on July 17, 1924, at 438 Ilchester Ave., in Baltimore, Maryland. It’s been said that if you have something significant happen to you, you will always remember it. And I remember so much of my life, good events and bad.

When I was three years old, my mother was in the hospital and my father took me to visit her. On the way inside, I took three stones off a planter and put them in my mouth. When I got to her room to see her, she looked at me and said, “Bobby, come here.” I shook my head no, and refused to go.

Then she said more sternly, “Bobby, I said come here.” So I did. And she scooped the stones out of my mouth and asked me, “What did you do that for?”

I said, “Mommy, I brought you present.”

This is my first memory. My mother kept those stones until she died at 105 years old.

Every summer, from the age of six to sixteen, I stayed with my grandparents in Virginia. My mother had her own business as a beautician, and she couldn’t watch me and run her business at the same time. My parents remodeled our home so that the kitchen was downstairs and the beauty parlor was on the first floor. At that time, it cost 25 cents for a woman to have her fingernails painted, and the same amount for a shampoo and to have your hair set.

At the end of every summer, I didn’t want to come back; I guess you could say I was over-loved.

In 1939, I dropped out of high school and started an apprenticeship as a tool and die maker. I didn’t want to be drafted into the army, so I enlisted in the Navy on December 12, 1941, five days after the bombing of Peal Harbor.

I was 17 years old when I first attempted to join. I brought the papers home and gave them to my Dad to read and sign. He read them and looked at me and asked, “Are you sure?” And I said, “Yes I am.” So he handed them to my Mom, and she started to scream. She said, “No enlisting now.”

Drafting began when you were eighteen years old, and I didn’t want to be drafted. I wanted to choose my own path and go into the Navy. But my mom wouldn’t sign the papers. So I had to wait three months or so, until I turned 18 and could join on my own.

There were twenty-six houses on each side of the street that I lived on in Baltimore. And there were 48 people from them who served in WWII. It was the largest entry of males and females into the service of any city in the U.S. To celebrate, they hung a cable across the street and suspended the American flag from it, as well as a flag with the same number of stars on it as people who had volunteered from our street.

At the end of the war, all 48 came back alive. And we had all been in every branch of the military— Marines, parachute jumpers, Army, Navy. And there were no hazards either. I guess we were street smart. And those on submarines, which I was, suffered a 53% casualty rate– the largest percentage of death tolls of all branches of the military.

Because I had two years under my belt already of real-world experience, they automatically gave me a designation of MM2C— a motor mate second class. That was my rating. I served in the Navy until two months before the end of the Japanese surrender in World War II.

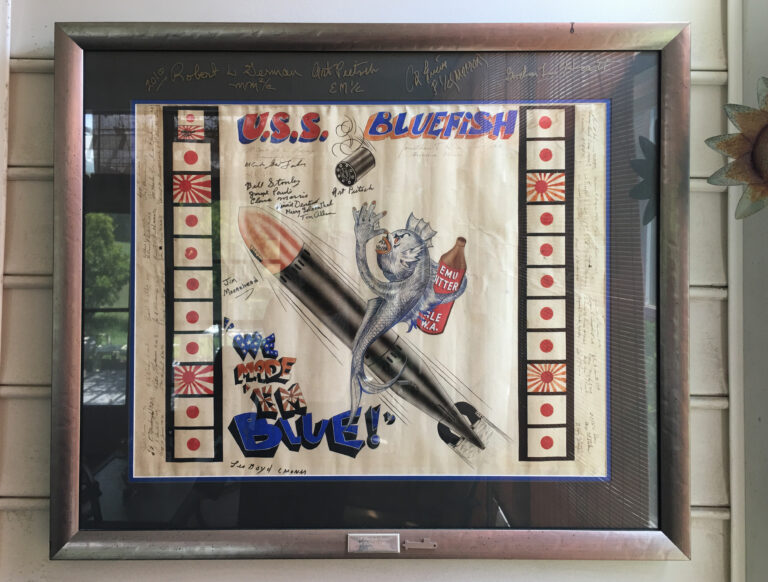

During the time I served in WWII, I made three patrol runs. Two on the submarine Angler 240, and one on Bluefish 222. Those submarines sank 30 enemy ships during the war.

We set off from Midway Island on our first patrol run, and we hit a small patrol boat and sank that with our deck guns. Three days later we came across four Japanese convoy ships that were headed for the Marshall and Gilbert Islands to resupply the enemy with soldiers and supplies— two tankers and two merchant ships. We carried twenty-four torpedos with us and used well over half of them in sinking those four ships. So we turned around and headed back to Midway to refuel the boat. After three days, a Japanese submarine spotted us on the surface and shot four torpedos at us. We didn’t have anything to attack them. But we managed to escape.

After we refueled, that’s when we were sent on a rescue mission. There were American, Dutch, English, and Philippine citizens trapped on the island of Panay. They were being protected during the war by the guerrilla natives of Panay, who were hiding these people in the jungle and in caves. If the Japanese had found them, they would have suffered terribly at their hands.

The guerrilla chieftain had sent word to General McArthur in Australia to coordinate a rescue mission. The Japanese were hiding all throughout the area, but they didn’t spot our submarine, and we slipped between the two islands of Manilla and Panay, and reached the China Sea, on the left side of the island.

That night, when we surfaced, the guerrilla chieftain came out to greet us from a dugout canoe and told us he had 58 people— and asked us how many people we could take. We had anticipated 12, but my skipper, Robert Olson, was a super guy and a great captain— he replied that we could take them all.

And you can’t imagine happier people than those 58. Women and children were in the forward torpedo room and officer’s quarters. There was one seven-month pregnant woman, a four month-old baby, and a couple of elderly women and young girls. We put the men and boys in the after-torpedo room. All 70 of us crew members cross-bunked, meaning, when we got off watch, whatever hammock was available, that’s what we crawled into to sleep.

We had them on board for sixteen days and nights until we reached Darwin, Australia. One of those teenage girls met one of the sailors who was keeping watch in the torpedo room. They became friendly and decided to get married after the war. And they named their first child Angler, after our submarine.

When we reached Darwin, we had a feast and a party.

In the Navy, after you made a patrol run, 15-20% of the crew would be off the boat and into the relief crew. So I joined relief crew and remained in Australia for the next three and a half months. I had the job of chauffeur for the squadron commander— a very cushy job.

The commander had an Australian girlfriend, and they spent a lot of time together. Every morning I would pick him up, then her up, and then their friend, who had a chicken farm. I must have been the only GI who was having bacon and eggs every morning for breakfast.

At this time, there were no young males in Australia, because everyone between the ages of 18 and 48 had been drafted. So the only males were those coming in off the submarines. About a week into my new post, the commander’s girlfriend said to me, “I have a friend and I told her about you. She’d like to meet you.”

So I did. And I rented a hotel room when we met, and we lived there together, Heidi and I, for the next three and a half months. I knew I couldn’t stay as a chauffeur forever, but I didn’t have the heart to tell her that I had to go back to sea permanently. There was nothing I could have done; if I had deserted, I wouldn’t have been allowed back into America.

I left on July 19. And neither of us knew that she was pregnant. The Australian government had stopped publishing any birth or death records because they didn’t want anyone to know that foreign soldiers were back there helping out with their breeding system; so I never knew.”

To be continued…